Review

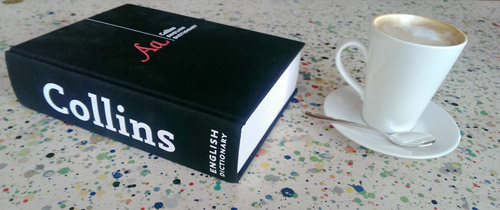

Collins English Dictionary (12th Ed.) 2014

Collins

Hardback 2300 pp

"I challenge you to find a better, more current dictionary of English in book format than this new Collins dictionary."

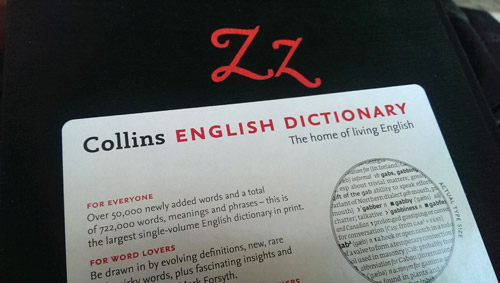

When the people at Collins said they were sending me a copy of their latest dictionary I never could have guessed what a whopping big book it would be. It arrived by courier in a shipping bag as large as a pillow. It is no wonder that it is being touted as "the largest single-volume English dictionary in print".

On first impression it is beautiful. The funky hard-back binding is of embossed black cloth with elegant and contemporary typography front and back, doing away with the pesky paper jackets that only ever wear and tear with time. This provides good grip. It is a great strategy by Collins to depart from the staidness of its competitors by adopting a modern look and feel in the age when everything is screen-based. This is a dictionary that announces its presence on the bookshelf.

A friend of mine asked me, "How different can a dictionary be?" While look and feel is one thing, the more important differences are, of course, found in the contents.

Most up-to-date on the market

The major selling point and raison d'etre of this new an improved, Twelfth Edition of the Collins English Dictionary is that it is not only comprehensive – with almost 200,000 entry words – but that it is without doubt the most up-to-date dictionary on the market.

The major selling point and raison d'etre of this new an improved, Twelfth Edition of the Collins English Dictionary is that it is not only comprehensive – with almost 200,000 entry words – but that it is without doubt the most up-to-date dictionary on the market.

There is a natural tendency to be sceptical of the selling point is that some 50,000 new words have been added but scratching below the surface this makes sense. It isn't that 50,000 new, nonsensical words have been invented in the time since the last edition but that too many everyday words have been excluded from past editions. This will no doubt settle many an argument during games of Scrabble.

Too many dictionaries claiming to be new are rehashed older versions sprinkled with new words. The new Collins dictionary comes across as being thoroughly overhauled and well thought-out. Just what you want from any new dictionary.

While it does include fresh new words like malware and zip file alongside headline-grabbing additions such as twerking, twitterati and bling – but curiously not selfie, the more important additions are words that somehow never make into other dictionaries despite being established.

A good example is my pet dictionary peeve, diabetes. In Samuel Johnson's day the 1755 entry read, "a morbid copiousness of urine". Yet, 90 years since the discovery of insulin and the distinctions between Type-1 and Type-2 diabetes, the majority of dictionaries have not kept up to date with good definitions. Until now, that is.

The work that has gone into this entry alone by including separate head words for diabetes insipidus, diabetes mellitus, diabetic and diabetical, demonstrates that this new dictionary is leagues ahead of the pack. No rehashing of tired old definitions here. No one wants a dictionary that still describes wireless as 'a cordless radio'.

The Joy of Dictionaries

Perhaps equally contemporary is the inclusion of an introduction my author Mark Forsyth, known for his smash The Etymologicon, about the joy of dictionaries. This, again, is a move away from the stuffy type of introduction that can be found in rival dictionaries. This underscores what the editors at Collins have tried to do in terms of repositioning their dictionary in the electronic age.

Now, the point of a dictionary is of course to be authoritative, not popular. Have no fear.

Their entries are informed and up to date. Unlike many dictionaries, the definition of inflation correctly maintains in economics terms that the phenomenon is one of rising prices resulting from an expansion of the money supply – not vice versa, as in many other dictionaries.

There are many, many important scientific and technical words among those 50,000 new additions. This is evident in the inclusion of Higgs boson, Higgs particle and the informal God particle. Important, contemporary science words such as peptide, unununium and a note that there are currently 118 elements so far known to man.

In the world of Wikipedia and misinformation on the internet, the inclusion of so many up-to-date terms makes it a must-have dictionary.

Place names, proper nouns and names

This review is not all roses, however. While examining the dictionary something jumped out at me that took me by surprise: an entry for Versace, complete with information about both Donatella and Gianni. This, to me, was an odd thing to find in a dictionary of all things.

This discovery led me to look up other famous people that I could think of. Yep, Obama is there, both presidents Bush, Julian Assange, Alan Turing, Mark Twain and Noah Webster. The entry for Malcolm X was under 'M' not 'X', and there was an entry for Chanel, real name Gabrielle but known as Coco, reads the entry. I found this quite disturbing. I am not used to these types of things being in my dictionary. With 5500 people included, I now understand where at least some of those 50,000 new entries came from.

Delving deeper, there are entries for old city names (Bombay, now Mumbai), mountains I will probably never refer to (Mont Bona, Alaska – height: 5005 m) and even Bondi Beach, Sydney. In a dictionary, why??

It's all about the words

Anyone who needs a dictionary for editorial and house style purposes will require just that bit more from their dictionary than definitions. An all-important distinction is – while trivial in everyday terms – typesetting and editorial consistency. How does the new Collins dictionary hold up in these regards?

Americans never need to worry about alternative spellings as much as those wedded to British English. That is because Noah Webster did them the favo(u)r of streamlining many spellings (thanks to him, all English speakers write women and not wimmin as standard). A good yardstick of any dictionary is the editorial decisions behind which spellings come before others.

Every editor knows that consistency is key – spelling is never personal. The game I like to play with any dictionary is how do they treat the past participles of the following verbs (See Chapter 55 in my book, The Joy of English): burn, dream, dwell, spell, spill, knit, spoil, learn, lean, leap, light etc?

The choice in British English is, does the -ed spelling come first or the -t spelling? Collins is decidedly in favour of -t spellings first, -d spellings second with 9 out of my list of 13 verbs. Four of these verbs were -d first, -t second. This is near consistent but not fully (still better than many other dictionaries).

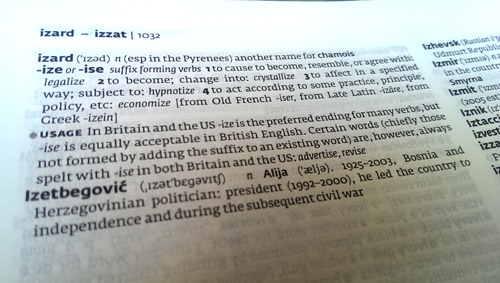

The next thing to check in any dictionary is whether they are -ise or -ize spellers. Collins likes the latter, but at least they acknowledge "or -ise" alternatives.

In this regard the entry for -ise or -ize adds a rather misleading addition on usage, stating: "In Britain and the US -ize is the preferred ending for many verbs." Not true. It is the standard form in the US and one of two forms that are standard in Britain.

What dictionaries never really point out is that in the British news media (the BBC, every daily newspaper, all magazines, the Economist etc), the entire British boards of education and most corporations use -ise spellings as standard, while -ize forms are de rigeur among British general book publishing, science publishers and academic circles – including the publishers of dictionaries – as part of their accepted house styles.

Moving swiftly on, I was also disappointed that the editors at Collins haven't taken a stricter line on their choices concerning italics. Again, this stuff matters mostly to editors – although they should learn them – often need to look up words to know whether it is current praxis to italicise foreign words.

Of the list of a dozen or so words that the Economist Style Guide recommends italicising, the Collins dictionary does so for in situ, raison d'etre and coup de grace. It does not, however, italicise coup detat, ad hoc, en masse, avant-garde, vice versa, et al. or vis-a-vis.

On the other hand, it does italicise the following: mal de mer (French for sea sick – why??), vers libre and vin de pays. Although useful ... including these really isn't that useful, italicised or not.

This mish mash is a half-way step towards the newest Oxford dictionary, which did away with indicating italics almost fully. Given that I still keep an old Oxford dictionary on the shelf solely because it retains italics for these and other entries, it is sad that the Collins doesn't make that faithful old dictionary redundant by including more italicised words for editorial reference.

Clear etymology and entry words

Getting back to things that are great about this dictionary, I was pleasantly surprised by the clear, concise format of the all-important etymology sections. They stand out well and read easily, presented in reverse chronological order.

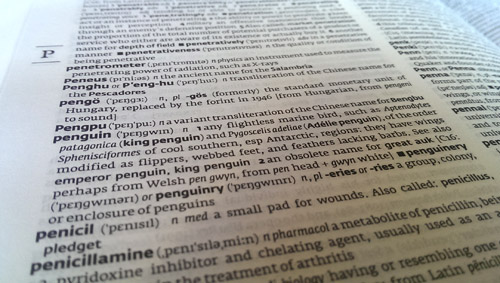

I am glad to see that the editors of Collins managed to include the etymology for penguin as coming from Welsh pen gwyn, or pen head + gwyn head. This is the first British dictionary that I have seen to date that includes this information about the most famous Welsh linguistic export – something that Webster's has included for decades. (Other dictionaries usually state: origin unknown.) This is further confirmation that this new dictionary has undergone thorough reworking.

When it comes to capitalisation, another standard test of any dictionary is to see how they treat wine varietals/varieties. To capitalise or nor capitalise. The Collins editors went for the former – it is Malbec not malbec – which is the usual editorial choice for grape varietals in UK wine writing but often the case in the US.

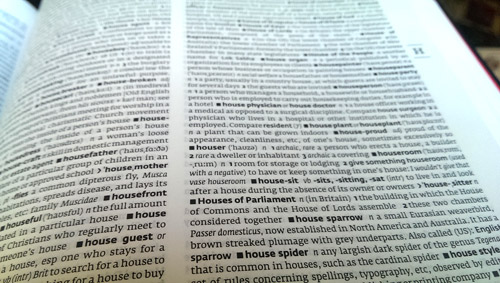

One area where this dictionary excels, in my opinion, is in the formatting and typography used to make words stand out for easy scanning. All entries use bold sans-serif fonts while definitions are in roman serifs, making for great contrast and easy searching. Individual words pop out of the page.

The layout is clean and the dark quality printing (possibly rich black?) is crisp and clear on the bleached-white pages. The paper is marginally see-through but with more than 2300 pages the balance is just right. This book weighs in at an impressive 2.6 kg.

In fact, size is another of the publisher's selling points for this book. So, how does it compare with other dictionaries out there? Well, as you can see from the photo it is larger than the Oxford Concise and smaller than the two-volume Complete Oxford and Webster's Third dictionaries. It is the same size as the folio edition of Johnson's famous dictionary. The large lettering on the spine clearly commands attention.

No shirking or taboo words

Another hallmark of a good dictionary is in whether or not it chooses to include swear words and other taboo entries in its pages. The editors at Collins have thankfully decided against banning any words.

The entries include all of the boyhood favourite words to look up, including the c-words, f-words and s-words. Although the editors don't yet pass judgement on the increasingly taboo in the US v-word, it does bow to political correctness by stating that both redskin and squaw are taboo – even though the two words that have been slandered in the past century to be awful despite being etymologically in the clear, according to author and lexicographer Michael Quinion.

Conclusion: my new go-to dictionary

Summing up the plusses and the minuses of this new release, the fundamental question remains: will it replace my current dictionary? Despite the minor shortcomings with the italics and including way too many famous people among its definitions for my liking, the overwhelming comprehensiveness and unrivalled newness of the words and definitions featured in it mean that this will now be my new go-to dictionary of choice.

I challenge you to find a better, more current dictionary of English in book format than this new Collins dictionary.

Jesse Karjalainen is the editor of whichenglish.com, the author of The Joy of English, as well as Cannibal and Roanoke, part of the Transpontine Series of books covering the language and history of the United States.

Copyright 2014–2015 | whichenglish.com